Ansley Park

At a gathering of members of the Ansley Park Civic Association (APCA) this fall, neighbors discussed the upcoming tour of homes for the next year. It would be the first since the start of the pandemic and turnout was expected to be high. One resident asked if the event should be used to raise funds for anything in particular to motivate more donations. Snidely, another replied, almost under his breath, “the APCA legal defense fund?” (Note: this does not yet exist.)

1. History

After countless millennia free from any known real estate speculation or civil litigation, the land that would become Ansley Park entered the possession of the United States through an 1821 treaty with the Creek Nation. The land from that treaty was then divided and distributed through a lottery. George Washington Collier, who had lived on an adjacent homestead since 1822, purchased the 202.5-acre parcel in 1847 for $150. For many years, his nearest neighbors were in the native American village of Standing Peachtree and he claimed to know the tree for which Peachtree Street was named. His home, in the adjacent neighborhood of Sherwood Forest, is thought to be the oldest house still standing in its original location in the city.

George Washington Collier House, not actually in Ansley Park.

The Piedmont Driving Club was founded as a social club for the elites of Atlanta to drive horse-drawn buggies on the outskirts of the city in 1887. In the 1890s, multiple successful expositions were held on the portion of the club’s grounds that would become Piedmont Park. In 1896, the year after the Cotton States and International Exposition, a lawyer turned real estate developer named Edwin P. Ansley began pestering Collier to sell. Their deal fell through multiple times over the next several years. Fortunately for Ansley, Collier was debt-burdened and soon-to-be deceased.

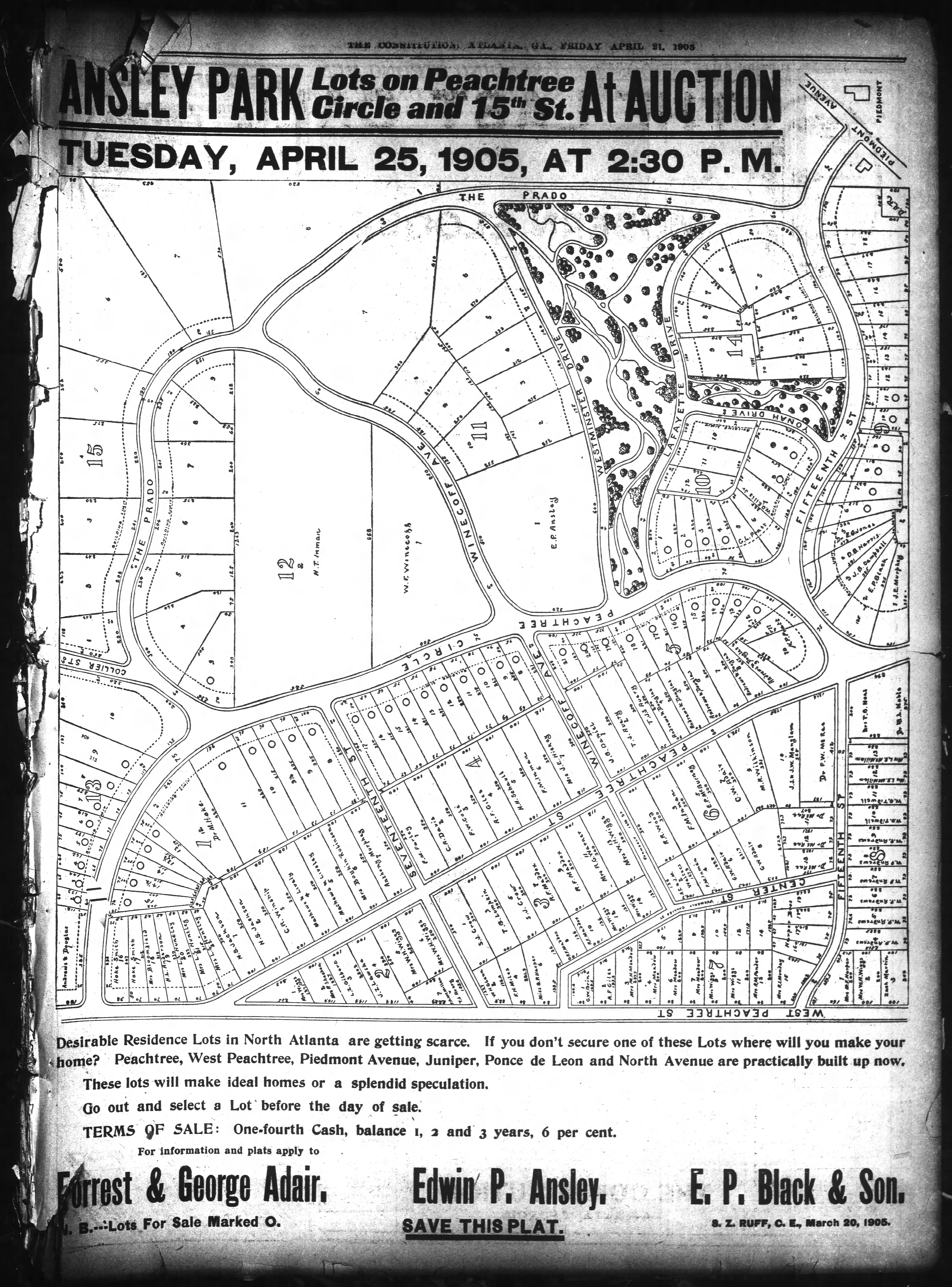

In 1904, his heirs were ordered by a judge to auction 200 acres near Peachtree Street in one complete block. The bid was won by Ansley with four financial backers, including Hugh T. Inman, whose brother gave his name to Atlanta’s first suburb, Inman Park in 1889. The first lots were sold with 3 restrictions:

- lots were to be used only for residential purposes;

- no house could be built beyond the setback lines backed on the plat maps; and

- no property could be bargained, sold leased, or otherwise conveyed to any person of African descent.

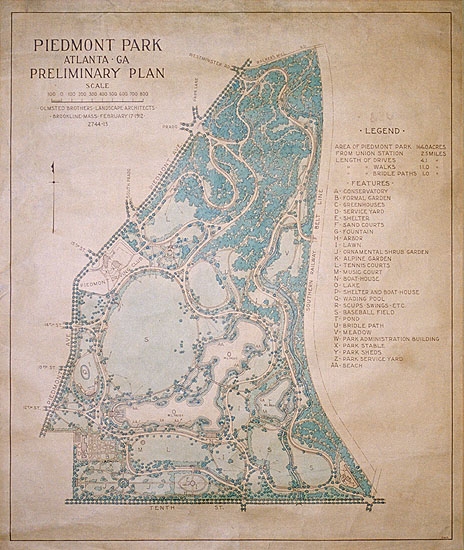

In 1909, the City of Atlanta purchased Piedmont Park from the Driving Club and began work on plans to develop it as an Olmstedian public park. Solon Z. Ruff Jr. designed the streets of Ansley Park according to the same principles, which he learned while working for Oldsted as chief surveyor in the planning of Druid Hills. The wide curvilinear road cut through a neighborhood connected by a network of small parks. The second golf course in Atlanta was added in 1905 on the floodplain at the north end of Ansley Park.

The Olmsted Brothers’ 1912 Piedmont Park Master Plan

Like other advertisements from the era, the early Ansley Park ads have an amusing candor interrupted occasionally by horrific racism. One ad boasts “its value has INCREASED 11,210 PERCENT. in nine years. […] It has not and NEVER WILL HAVE a store, a garage, a factory, a hospital, a sanitarium, a shop of any kind. Deed restrictions keep them out permanently. It has not and never will have a home belonging to a person of color or occupied by one other than as a servant on the premises.” That particular ad is estimated to be from around 1915, nine years after the Atlanta Race Massacre. Another ad contains an anecdote of a resident making “a profit in less than 9 years of more than 512 per cent.”

Ansley Park was marketed as the Atlanta’s first automobile suburb. Although the term sounds redundant today, the streetcar suburb was dominant at the time. A blub in the Atlanta Constitution in 1905 read “in the very near future those who own homes in Ansley Park are going to sit on their verandas and see among their neighbors the best people in Atlanta and on the boulevards before their doors everybody who rides, drives, or ‘motors’ an automobile, for all roads must lead to these, the only driveways in Atlanta.”

A 1905 advertisement in the Atlanta Constitution. These lots will make ideal homes or a splendid speculation.

Ansley’s dream was for the neighborhood to become an exclusive enclave of mansions near the Driving Club. He did succeed at first, selling very large lots for numerous palatial mansions. One of the most notable mansions was his own: the Granite Mansion, a 15-room, 10,000-square-foot home with a carriage house in the back that was itself big enough to live in. He began to compromise on that vision of the community as early as 1908, when he began developing smaller lots for middle class families in hillier, less convenient areas.

Edwin Ansley’s home: the Granite Mansion.

In 1913, Edwin Ansley suffered a stroke. By 1918, he sold the home pictured above. One year later, he lost the Golf Club to foreclosure and relocated to Brunswick. In 1923, he died of a second stroke. His fortunes changed with the stroke, but a slow down in construction during World War I spelled his financial ruin. By 1919, new one-story homes outnumbered two-story homes and apartment buildings were being added on the periphery. Twenty-two apartment buildings were added between 1919 and 1929 (2/3 of all that has been built in Ansley Park as of 2004). Duplexes were scattered across the neighborhood.

1 South Prado, also known as the Della Manta, an apartment building designed by Neel Reid in 1917, was the home of Margaret Mitchell after she published Gone with the Wind. Like almost all apartments in Ansley Park, it was converted into condos.

In 1925, the Granite Mansion became the Georgia governor’s mansion. Ansley Park was complete in 1934, when the descendants of George Washington Collier decided to develop what became Sherwood Forest, adding 65 more lots to the northwest.

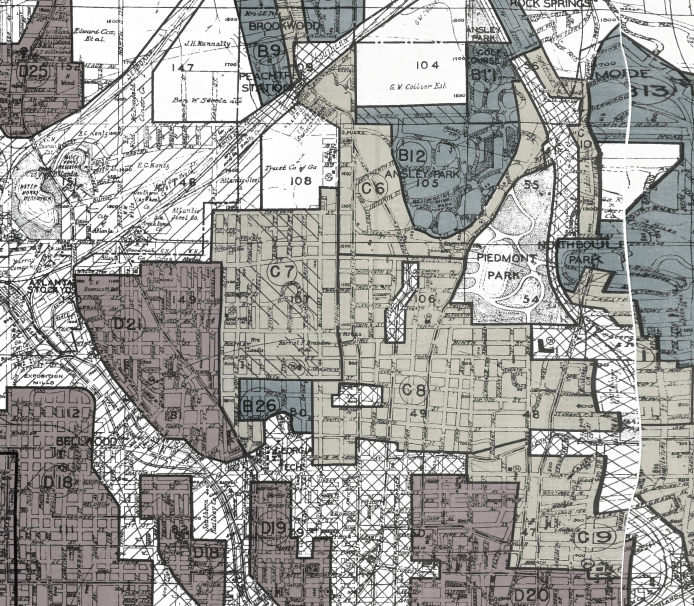

The Mapping Inequality Project on redlining during the New Deal era shows Ansley Park divided into two zones in the 1938 map. The central parts received a B: “the oldest still desirable area in the city [..] future outlook for property in this area is slowly downward; hence, if property is acquired in this area, it should be sold rather than held.” The periphery of Ansley Park received a C: “most of the city’s largest apartment houses are in this area which is desirable rental area because of transportation facilities and proximity to the center of city.” The transportation facility mentioned were streetcars along West Peachtree St, Peachtree St, and Piedmont Ave. It is also worth noting that both zones have 0 percent foreign-born, black, or relief families.

The redlining map of Atlanta in 1938, showing Ansley Park in yellow and blue

As we know, these New Deal era maps were self-fulfilling prophecies. Although Ansley Park remained overwhelmingly white, even after desegregation, its social composition changed dramatically in the post-war period. From 1940 to 1970, 307 dwelling units were added without building a single freestanding apartment building. The large homes were divided into apartments and boarding houses while their massive lots were subdividing repeatedly. The number of duplexes grew 93 percent and multi-family homes by 28 percent from 1954 to 1964.

229 The Prado, an originally single-family home that was converted to a multi-family home at this time. It has since been converted back into a single-family home.

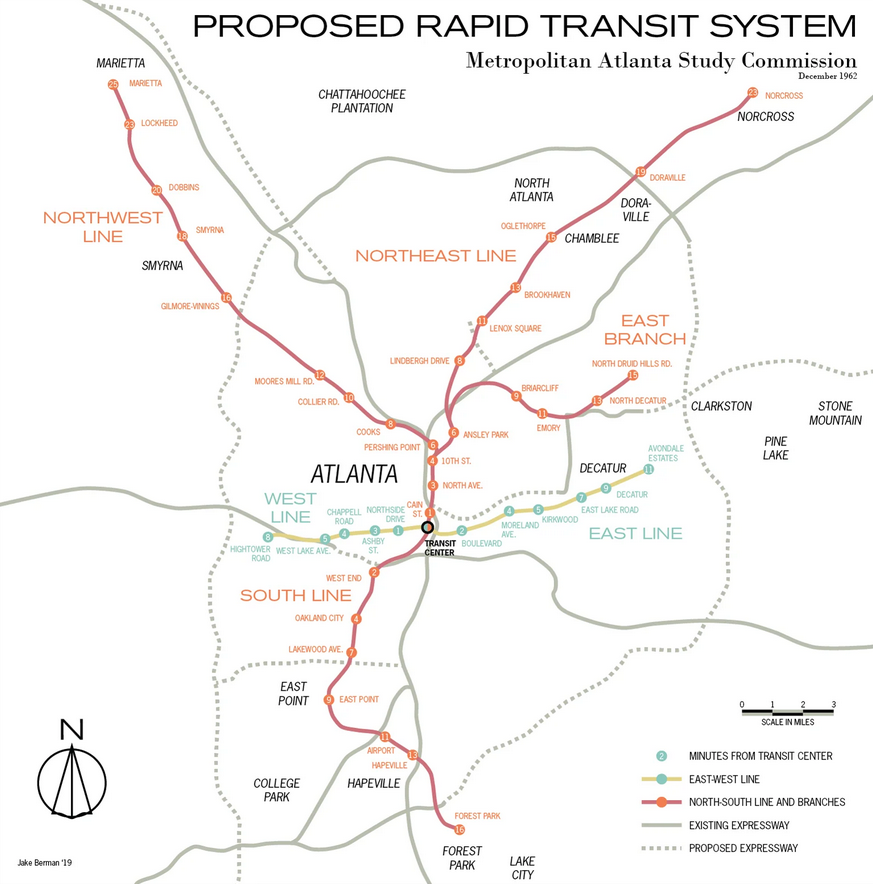

In 1962, the first MARTA plans were proposed, including a station labeled “Ansley Park.” The Intended location was on Peachtree at 17th St. A group of residents around that time transformed the Ansley Civic Club, previously a purely social group that began in 1915, into the Ansley Park Civic Association (APCA).

The proposed 1962 MARTA plan. This map was created by Jake Berman at 53 Studio based on older maps that would not look as good on my website.

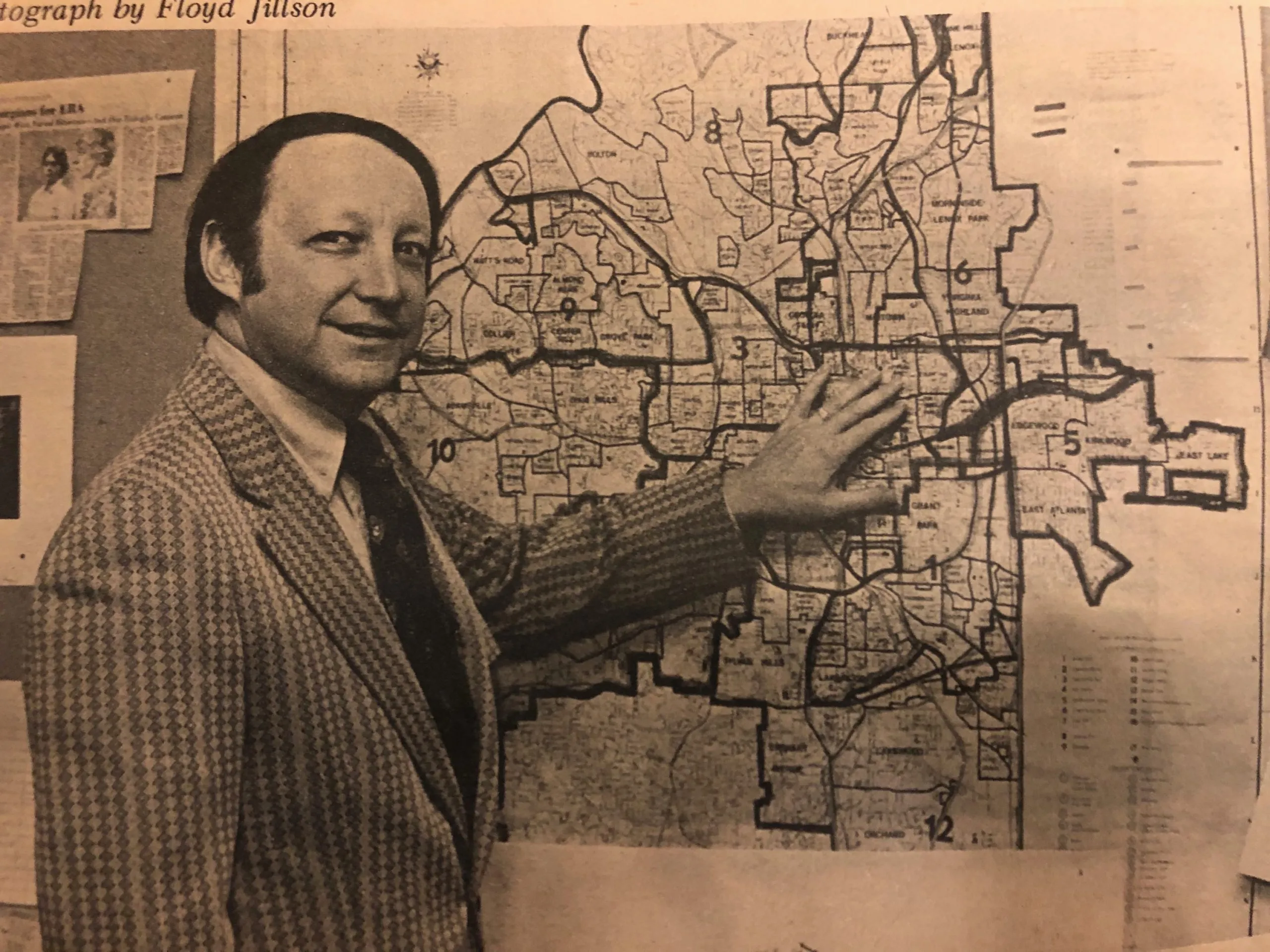

The APCA did not only form around opposition to transit. In 1964, they commissioned Eric Hill and Associates to conduct a conservation study. They then campaigned to enforce zoning laws and housing codes. One report estimated 10 percent of all structures in the neighborhood were rooming houses. The association’s pro bono attorney at the time summarized their goals. “The policy was basically ’no commercial development in Ansley Park’ and whenever we had an opportunity, reduce the density of residential property.” The association did still approve some additional density in the period, including the Westchester Square Townhouses. This was also the period that Leon Eplan, who would become Mayor Maynard Jackson’s Commissioner of Budget and Planning and set up the NPU system, decided to make the neighborhood his home. Eplan had also been the chief planning consultant for designing MARTA, promoting denser development around stations. He often assisted the neighborhood in its own plans.

Former Ansley Park resident, Leon Eplan.

Attendance at zoning meetings began to reach record highs and developers began to approach the neighborhood with caution. Ansley Park began to earn a reputation for legal action that it maintains today. Perhaps surprisingly, one project that was not blocked was the development of public housing in the neighborhood, which is one of only 9 Atlanta Housing Authority-owned communities to survive the Neoliberal era (so far).

The changes to the neighborhood in the 1960s were symbolized by the loss of the governor’s mansion. Edwin P. Ansley’s former home was one of many that had fallen into disrepair during that era, at the same time that public protests had become a popular tactic of mass movements. Lester Maddox, remembered today for his racism and support for segregation, was unpopular among other residents of Ansley Park at the time for those same reasons. He relocated the governor’s mansion to Buckhead and the mansion was sold to an attorney who despised Maddox, David Harris. In 1969, Harris threw a “phooey party,” named for the governor’s favorite epithet, that remains legendary in the neighborhood today. The same hippies who had protested outside the mansion are shown in some photos on top of it, with a large peace sign hanging in the window. Over 400 guests attended until police arrived around 10pm. The next day, Harris had the mansion demolished. He moved into the two-story carriage house, subdivided the grounds, and sold 4 lots from the land where Ansley’s home had stood.

The stage of the Phooey Party, celebrating the departure of a segregationist politician from Ansley Park, before destroying one of the most historic homes in it.

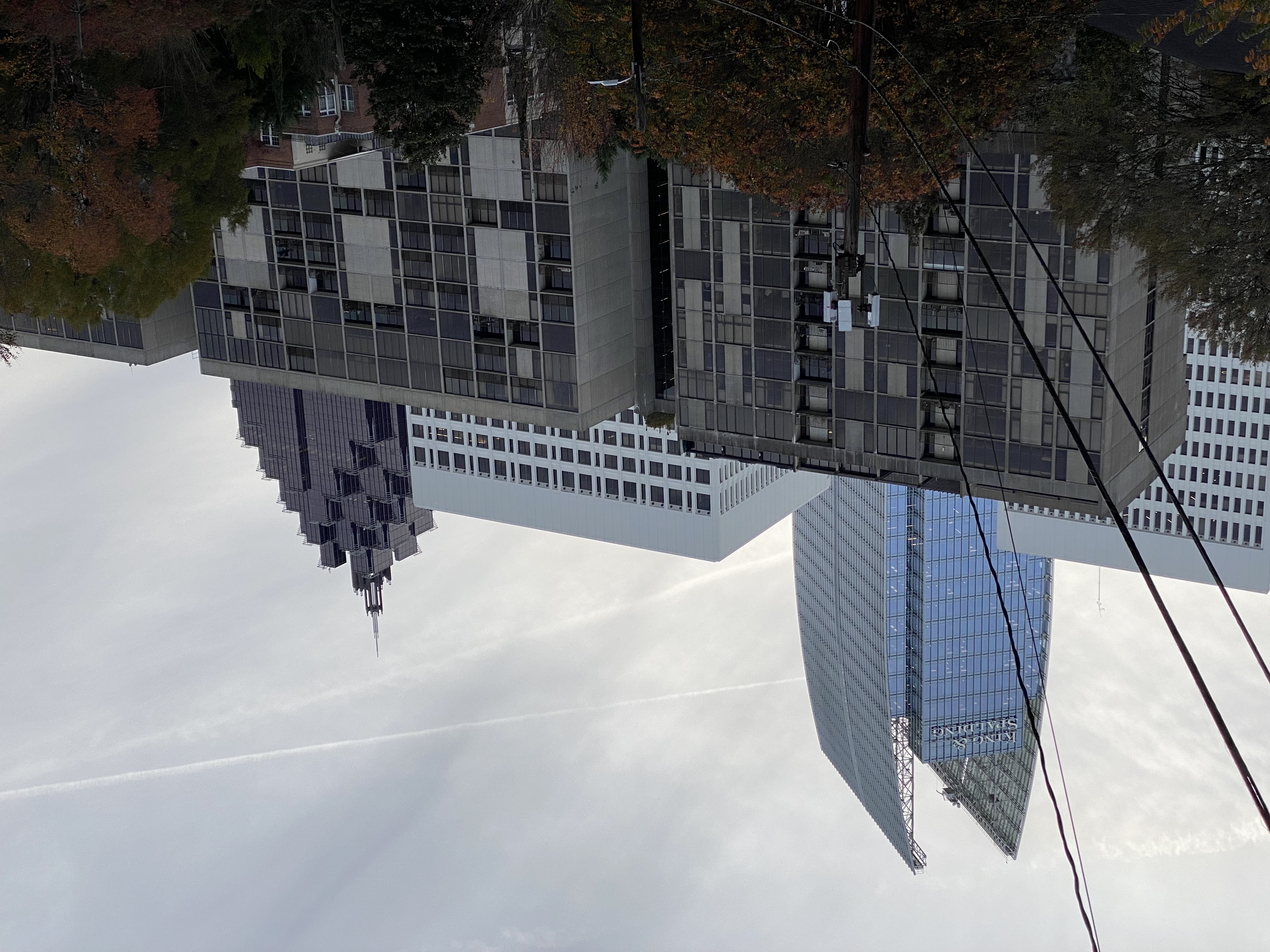

In the same year that Ansley Park’s most historic home was demolished in the coolest way possible, on its periphery 12 acres were assembled for one of the largest construction projects in Atlanta’s history. Jim Cushman planned to build “the world’s first micropolis.” In today’s terms, Colony Square was the first mixed-use development in the Southeast. The architect, Henri Jova, was inspired by the movements associated with International Style, influenced specifically by Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation.

The block the development would rest on contained 131 housing units (115 renter-occupied), which would also probably have been some of the oldest. By all accounts, the area at that time was largely populated by hippies. Ultimately, the APCA even gave its reluctant support to Colony Square’s design after conceding that commercial development on Peachtree was inevitable. It opened in 1975 and filed for bankruptcy the same year. It is also where I live.

Colony House and Hanover House, the two condo buildings in Colony Square, are considered a part of Ansley Park only when it is convenient. (My own unit is in this photo.)

During the era of boarding houses, Midtown, especially the area immediately south of Ansley Park called the Strip, was the heart of hippie counterculture in the region. It had a reputation for porn shops, lawlessness, drug use, and violence. One resident I spoke with likened Ansley Park in that period to Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco. All those things began to decline steadily in the 70s. A study of housing market activity in Atlanta in 1983 suggested that Midtown, and presumably much of Ansley Park as well, was undergoing intensive gentrification. That study did not discuss the sexuality of the gentrifiers, but historical accounts have indicated that from the early 1970s on gays and lesbians began moving into older in-town Atlanta neighborhoods to rehabilitate properties (Doan and Higgins, 2010).

By the 1990s, the area was the heart of gay culture not just in Atlanta, but in the southeast. Ansley Park’s proximity not only to the queer institutions of Midtown, but also those of Cheshire Bridge Road made it prime real estate for a generation of gay “pioneers” to restore neglected historic homes and create a community for themselves. This area of Atlanta was both Haight-Ashbury and the Castro.

Today we memorialize a time when practically any gay person who wanted to live near Midtown could with a rainbow crosswalk at the intersection where Outwrite Books was once able to afford rent.

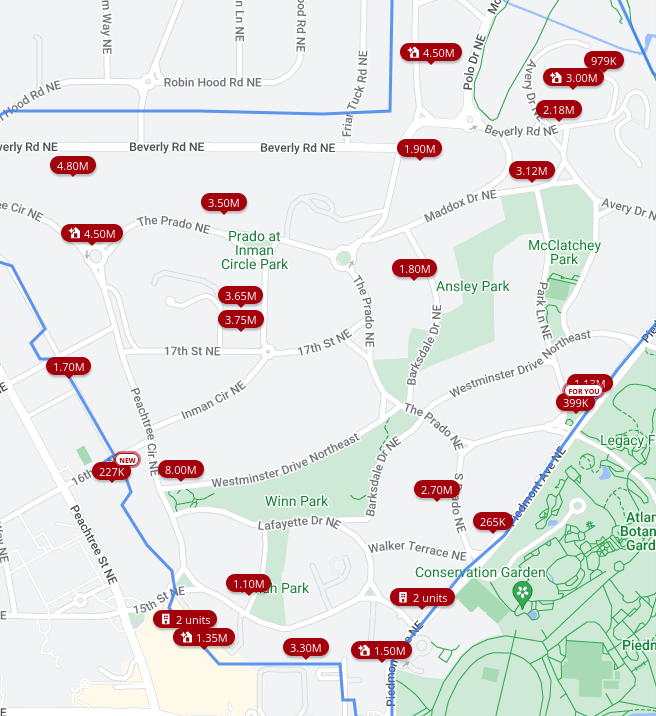

In the 1990s, an explosion of mixed-use, high-rise development in Midtown simultaneously made the area both more desirable to more people than ever and wildly unaffordable. The problem is becoming so severe that the Ansley Park is, for the first time since World War II, back on track to achieve Edwin Ansley’s dream of a wealthy enclave for elites.

I have saved you the trouble of checking how bad the problem is on Zillow.

2. The APCA

The Ansley Park Civic Association is the primary vehicle for citizen engagement in Ansley Park. Membership requires the payment of a recently increased fee of $100/year. Because of the high fee and the hostility that some residents have to the organization for its de facto role enforcing compliance with zoning and building regulations, many neighbors choose not to join.

As discussed earlier, the association was formed shortly before the push to site a MARTA station farther from Ansley Park than originally planned, to what is today the Arts Center Station. They have been instrumental in shaping Ansley Park ever since, especially through efforts to reduce density and prevent cut-through traffic. The association is organized into numerous committees, many of them corresponding to functions of local government: built environment, greenspace, history and preservation, traffic, and zoning. They also have committees for social events, security, and communications, which creates a regular newsletter called the Ansleyphile.

Two sibling organizations are connected to the association, but technically separate. They are the Security Patrol, which funds additional private security for the neighborhood with special care to the homes of donors, and the Beautification Foundation, which cares for and improves the network of small parks. Another major social institution is the Golf Club, where most of the APCA’s larger meetings occur. To join the Golf Club, five members of the club must sponsor a nominee who is then invited by the club’s board. According to two websites of dubious authority, the initiation fee is somewhere between $35,000 and $75,000 with monthly dues between $300 and $550. Although most of the residents probably do not belong to this club, those that do presumably have a lot of influence.

3. The Very Recent Past and Present

Out-of-control housing prices strengthen the analogy to famous neighborhoods in San Francisco and encourage tear-downs and speculation even in the absence of anticipated regulatory changes, like upzoning. Tensions in Ansley Park are high. There are many signs that dramatic shifts will be coming soon, feeding the anxiety of residents that the place they call home could be unrecognizable to them in 20 years. Their concerns are also not limited to the look and feel of the urban form, although one of them will almost certainly be in touch with you if demonstrate a misunderstanding the minutiae of the local regulations for your property. Some long-time residents perceive the changes to the social makeup that high home values bring and mourn the loss of the mixed-income community they moved into. Others oppose categorically any change that they can imagine lowering their property values in any way. Some probably manage to hold both of those views at the same time somehow.

There are three major regulatory changes underlying their anxiety. First, former planning commissioner Tim Keane’s Atlanta City Design plan calls for all land within 0.5 miles of a MARTA station to be rezoned for density. Second, the extension of the BeltLine on Ansley Park’s northern edge is nearly complete. Third, the city is on the cusp of a comprehensive rewrite of its zoning code. It is also relevant that the city of Atlanta implements its historic district regulations through zoning and has said that historic district rules will not be impacted by the overhaul. The first two relate as well, because residents worry that the addition of rail to the BeltLine will create a new station that mandates more permissive zoning.

A few years ago, a group within the APCA called Ansley Park Forever (APF) began lobbying the community to pursue historic district designation from the City of Atlanta, which would protect historic buildings from demolition and certain alterations. Although the neighborhood has been on the National Register since 1979, that status only confers protection from federally funded infrastructure projects and grants tax incentives for the owner of a contributing building to undertake preservation work. In 2015, Ansley Park updated its listing to remove dozens of properties that had been altered too dramatically or demolished entirely, bringing them down to somewhere around 65% of structures contributing (the usual cutoff is 50%). Then, last year, the same group successfully nominated Ansley Park for the Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation’s Places in Peril list of endangered sites.

When APF tried to gauge community support for a historic district, they found more residents more skeptical of how it might affect them than supportive. Another group formed, called Advocates for Ansley Park (AAP), to champion the “property rights” of homeowners and oppose the creation of a historic district. They argue that residents should be able to change anything they like on a property that they own and historic district status would lower property values. They also suggest that homes be protected on an individual basis through measures like preservation easements.

The conflict between the two groups came to a head when AAP sued the APCA last year over the issue, precipitating the resignation of four board members and the dissolution of APF. AAP still exists, or at least still has a website as a warning to anyone who might consider seeking historic district designation. APF not longer has a website to examine their views in writing, but Save Ansley Park does, and there is overlap between both the group members and the opinions expressed.

4. The Future and my Opinions

I believe that there is much about Ansley Park that is worth preserving. Despite the preposterous widths of its roads (not worth preserving), it is a delightful place to go for a walk—not because the homes are similar, but because there is so much variety in size, style, landscaping, and age while still feeling cohesive. Ultimately, I do support historic district status and created a map to understand the composition of the neighborhood better.

I do not agree completely with either community organization. Neither property rights nor the return on investment for someone’s house as a financial asset is important to me and I worry that historic preservation on an individual basis would only proliferate complex, unique, piecemeal rules across homes, if it were even possible to apply at the scale I want to preservation to occur. However, when I read Save Ansley Park’s website, I see scaremongering about density and transit-oriented development, sometimes even from the angle of their potential to negatively impact on home values (according to them). It frustrates me to no end that the political realities imposed by almost 100 years of publicly encouraged financialization of housing forbid us from acknowledging that home value appreciation and affordability are not simply different goals, but quite obviously opposites of one another. Similarly, I was uncomfortable with how triumphant the narrative in my two main sources of history were in their descriptions of multi-family housing converted back into large single-family homes. I understand this was in part because deferred maintenance would be addressed, but I cannot overlook that the elimination of boarding houses in Ansley Park did not eliminate the need for boarding houses of the people who stayed in them. It only eliminated their housing. Finally, advocates for the historic district occasionally use the term “naturally occurring affordable housing,” which I could only chuckle at the first time I read it.

It is clarifying to consider what they mean by that term anyway. The least expensive dwellings in Ansley Park are smaller, older units of multi-family buildings that do not have many amenities. Building housing that would be provided at a similar price to those units would be significantly less profitable for a developer than building at the higher end of the market even if it were permissible in the zoning, which I suspect it is not.. It is almost as naive to think that if we toss regulations out then developers will build the kind or amount of housing necessary to increase affordability “naturally” as it is to think that adequate affordable housing is already present “naturally.” They are, in fact, variations on the same misplaced faith in markets. One denies the problem, while the other insists that the solution to problems created by markets is more markets. Defenders of orthodox economics might insist that the market was not “free” enough and that was the problem. However, even in the simplified, idealized model, a market will not meet a universal need naturally because it will exclude anyone unable to pay the price at which suppliers break even. I believe that affordable housing does not simply need to be subsidized through programs like vouchers or temporarily suppressed rental prices, but removed from the market and managed in the public interest. Social housing, however, does not feel like a politically feasible recommendation, despite some of the last examples in Atlanta remaining in Ansley Park.

These condos are probably the kind of density we should expect developers to build in Ansley Park if we simply deregulate and allow more development. They would probably sell for over $1M each if not—according to rumor—for the discovery that the builder seems to have forgotten whether water flows up or down a slope when their balconies were being poured. If it is an option to sell six $1M condos with balconies that funnel rain into them, why should we expect developers voluntarily to create something affordable?

Doug Young, Director of Atlanta’s Office of Design, sees historic district status as assisting affordability by preserving a variety of home types and sizes in places where an unregulated market would replace most small homes with larger, more expensive homes.

Even if Ansley Park were as dense as Midtown, I believe that both would remain unaffordable. I do, however, believe that we have some obligation to increase density to allow more people to live in places like Ansley Park where they can drive less and access destinations more easily and enjoy a pleasant walk or bike ride. To that end, I think that the historic district would be useful, not to prevent density, but to designate where and in what form density can occur and facilitate development of more multi-family housing that resembles the multi-family housing already present in the neighborhood.

I will not pretend to know what that looks like in code after only a few months in planning school. Another observation by Doug Young was that people concerned about density are often in reality concerned about size and that was also clear in my conversations with neighbors. Footprints, setbacks, heights, and lot coverage were mentioned much more than number of units, which becomes a proxy for those characteristics to people who do not want more buildings like mine encroaching into Ansley Park.

Conversations about the housing stock that exists in Ansley Park, even among residents, often do not reflect reality. Although most of the land area quite visibly belongs to single-family lots and mansions are how the neighborhood is perceived, there are more condo units total. According to the Ansleyphile newsletter from June/July 2023, there were 635 single-family homes and 755 condominium units in greater Ansley Park. The 2015 update to Ansley Park’s entry in the Historic Register of Historic Places concluded by describing the neighborhood as “a stable middle- and upper-middle-class residential area.” I doubt the usefulness of those terms generally, but I would wager a guess at which group lives in which type of housing.

4. Specific recommendations:

1. Form a historic district for Ansley Park.

This will allow the preservation of a sufficient number of the historic homes in the neighborhood to ensure that it remains recognizable even if its zoning is changed. However, not every old home necessarily needs to be preserved as historic. The process of creating a historic district would offer an opportunity to consider which structures should be protected. The map above marks some of the more recently demolished homes in the neighborhood.

2. View the historic district as an implicit authorization of where development and additional density can occur. But do not equate density with affordability.

In the midst of a national housing shortage and in an already sprawling city with such high population growth projections, there is sufficient reason to argue for more density in a place like Ansley Park even without suggesting it will be the solution to the lack of affordable housing. As the surrounding area continues to develop, this is a neighborhood where people will be able to live a less carbon intensive lifestyle than most of Atlanta and we should make places like that accessible to more people. We should prioritize creating a diversity of housing options in such places through policies like inclusionary zoning and I believe that can be done in a way that respects what is currently there through the regulations for historic districts.

3. Involve residents as much as possible in the drafting of the zoning code and designation of the historic district, but limit the amount that neighbors can intervene in the development process to challenge a compliant proposal.

In Neighborhood Defenders, Einstein, Glick, and Palmer study the actions of groups commonly lumped together as NIMBYs, preferring the more neutral term ’neighborhood defenders.’ They explain how these groups tend to be unrepresentative of greater urban areas they belong to, how land use regulations accumulate to restrict the supply of new housing, and how those regulations create openings in the public engagement process for such groups to delay or prevent development. They also take care to highlight that the ability of residents in some places to block development has the effect of driving development into other less privileged areas with less organized resistance, promoting gentrification.

One of the most important tactics of such groups is to demand additional studies for things like environmental impact, noise, traffic, or parking, insisting on more studies until they obtain one with their desired result. One of the researchers’ suggestions is that which studies will be required be stated in advance of any public engagement process to prevent moving goalposts and shifting expectations.

Another point that the researchers stress is that neighborhood defenders are extremely knowledgeable about both local regulations and the public engagement process. In my experience, this is true. I do not personally have the knowledge to judge what the new codes in Ansley Park should be. However, I think that many residents, some of whom I spoke with, do and that the time they spent becoming experts on what does and does not conform with their neighborhood should be respected and drawn upon in the creation of the next zoning code. Specifically, I think that their input should be considered for things like the sizes and placement of buildings on lots.

There is, among everyone who has ever attempted to understand its application to a particular property, consensus that Atlanta’s current zoning code is unacceptably complex. It borders on unintelligible, having been crafted through the regular incoherent addition of ordinance after ordinance for decades without even the care to unify terminology across the code. Many of the rules have tables of seemingly quite arbitrary numbers intended to legislate something indirectly that could be made more clear if it were regulated directly. One of the biggest challenges in getting neighborhood approval of the rewrite will be persuading residents that many of the regulations that they think are protecting their communities are not the most effective way to communicate the outcomes they want. More than that, by regulating with less intuitive or less clear parameters, they don’t just prevent development—which some might be comfortable with—but they risk permitting something other than the outcome they wanted when a sufficiently dedicated developer ferrets out the many bizarre loopholes in a document like Atlanta’s code.

A map of nonconformities due to lot size, building coverage, FAR and/or use. Shades of red from light to dark are: use, form, both. An explanation of this analysis can be found in the link below.

To that end, the city began its outreach to neighborhoods with a study demonstrating just how many of the homes in Atlanta’s favorite, oldest neighborhoods are actually non-conforming with the current regulations. That document can be found here. At the bottom of the page, under reports, is an existing pattern analysis with a video explanation of the files and presentations at different scales. One of the neighborhoods in the study is Ansley Park, where they concluded “there is no consistent lot size” and “one-third of lots are non-conforming in terms of use, building coverage, FAR, or size but if setbacks were included, the number would be higher.” This actually makes Ansley Park one of the more compliant neighborhoods in the city with the existing code, especially among the older in-town neighborhoods.

4. Do not limit affordable housing policies to market-based solutions, especially in a place where the market rate is as high as in Ansley Park.

Policies like subsidies and inclusionary zoning should not be done away with but will only nibble at the edges of the affordable housing crisis. Within Ansley Park, there is already public housing in the Westminister community that should be expanded upon. The city can also assist non-profit housing development by cooperative organizations, community land trusts, or faith organizations like the Church of Christ, Scientist, a major landmark on the edge of Ansley Park that predates the neighborhood.

These are the public housing units owned by the Housing Authority of the City of Atlanta at Westminster and Piedmont.

If ever there has been “naturally occurring affordable housing,” it was the boarding houses that narratives of Ansley Park’s history celebrate the removal of. Despite standards often being too low, similar arrangements provided housing for people across the United States for generations and now many of the groups that cannot afford housing are the same ones who historically would have lived in them. According to the website of the Housing Authority of the City of Atlanta (AH), they now allow multi-family properties to include multiple single-room occupancy (SRO) dwelling units if they meet the city’s zoning requirements. Unfortunately, the current zoning regulations forbid them in most zones, including those of Ansley Park. So, my oddest recommendation is to bring back the boarding houses and SROs that once provided homes to a substantial portion of this community before they were excluded during its gentrification.

5. Make residents of Ansley Park aware that most of their neighbors live in condo buildings and that adding more living arrangements like those will not mean the loss of their community.

Even when we toured the city as a class, Ansley Park was described as a single-family neighborhood. Not only is this inaccurate today, but it has not been the case since some time in the 1920s. It was least true during the 1960s and 70s, when the grandest houses could not be preserved as single-family abodes and had to be converted into something that the people who wanted to live here could actually afford. A neighborhood is not just its buildings and Ansley Park’s buildings have adapted to suit different communities over its history. When we make decisions about our built environment, we are also making choices about who will live in our communities. If Ansley Park does not allow a greater mix of housing types, then it will become the exclusive elite enclave its founder imagined and future students reporting on it will have to write a lot more about the Golf Club.

Citations

- “Advocates for Ansley Park Website.” Advocates for Ansley Park. Accessed November 13, 2023. https://advocatesforansleypark.com

- Ariail, Donald. Ansley Park. Arcadia Publishing, 2013

- Ansley Park Civic Association. Ansley Park: 100 Years of Gracious Living. Ansley Park Civic Association, 2004.

- Ruch, John. “Ansley Park historic district idea sparks local battle over preser- vation and property rights,” October 2022. Accessed September 14, 2023. https://saportareport.com/ansley-park-historic-district-idea-sparks-local-battle-over-preservation-and-property-rights/columnists/johnruch/

- Doan, P. L., & Higgins, H. (2011). The Demise of Queer Space? Resurgent Gentrification and the Assimilation of LGBT Neighborhoods. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 31(1), 6-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X10391266

- Rankin, Ellen. (2015) “Developmental history/additional historic context information.” National Register of historic Places Application. Link.

- “ATL Zoning 2.0.” Accessed Jan 31, 2024. https://atlzoning.com/explore-and-learn/

- Einstein, Katherine Levine, David M. Glick, and Maxwell Palmer. 2020. Neighborhood Defenders. Cambridge University Press.